MINNEAPOLIS — There is a specific kind of arrogance that only exists in an 18-year-old male with a 3.9 GPA. It is a brittle, unearned confidence, the kind that assumes the world is merely a classroom waiting to be aced.

In the late spring of 1997, I possessed this arrogance in spades. I was done with my hometown. I was done with the river valley. I was bound for the University of Minnesota in the fall, but I couldn’t wait that long. I needed the city, and I needed it immediately.

So, I packed a bag and drove north with my brother. We were going to conquer Minneapolis. We were going to live the “Uptown Life.” Instead, I found myself three months later shivering in a hospital bed, my blood poisoned, my car stolen, and my ego surgically removed.

This is the anatomy of a summer that went wrong in every way possible.

The Landing

We didn’t hit the pavement running; we hit the carpet at Aunt Patty and Uncle Larry’s house. It was the necessary purgatory between rural safety and urban chaos. For two weeks, we were on our best behavior, sleeping in guest rooms and scanning the Star Tribune classifieds, circling listings for apartments we couldn’t afford.

But the pull of Uptown was magnetic. In the late ’90s, the intersection of Lake Street and Hennepin Avenue was the cultural solar plexus of the Midwest. It was grunge’s last gasp and the pre-dawn of the hipster era. It smelled like clove cigarettes, exhaust, and expensive coffee.

My brother, older and theoretically wiser, had a lead. He knew some girls from back home who had a place. We finagled our way in. It was a classic Uptown setup: creaky hardwood floors, too many people sharing one bathroom, and an unspoken agreement that rent was a fluid concept.

I had arrived. I secured a job at Urban Outfitters on the corner of Lake and Hennepin. This was the holy grail of retail. I was selling oversized denim and ironic t-shirts to suburbanites who wanted to look like they lived the life I was actually struggling to survive. I thought I had it made.

The Blowout

The disintegration of my new life began, as many tragedies do, with a birthday.

It was my brother’s birthday. The air was thick with humidity and bad decisions. We were drinking—cheap beer, probably whatever was on sale—and the tension that had been simmering between us for weeks finally boiled over.

I don’t remember the specific catalyst. It might have been money; it might have been a girl; it might have just been two brothers trying to occupy the same alpha space in a cramped apartment. But I remember the explosion. I remember deciding, with the absolute moral certainty of a teenager, that I wasn’t going to take his garbage anymore.

I went to sleep angry. When I woke up, the apartment was quiet. Too quiet.

My keys were gone. My car was gone. And my brother was gone.

He had vanished into the city grid, taking my only means of transportation with him. I was stranded in Uptown, a kid from the river valley with no wheels and a roommate situation that was rapidly deteriorating.

The Darkout

The universe, sensing blood in the water, decided to double down.

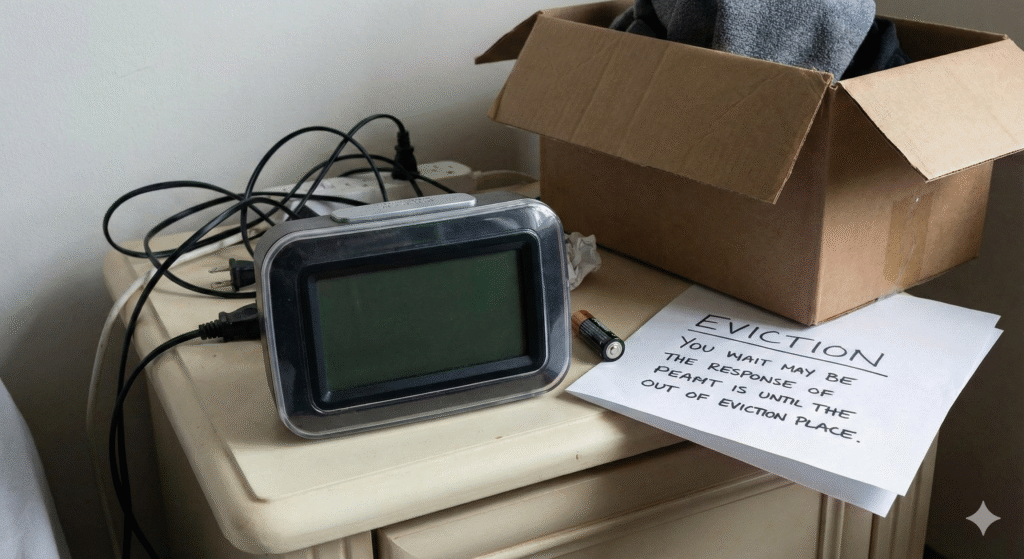

A few weeks after the exodus of my brother, the power grid on my side of the block hiccuped. It was a mundane infrastructure failure, likely a blown transformer, but for me, it was fatal.

In 1997, we didn’t have smartphones. We relied on General Electric bricks plugged into wall outlets. My alarm clock, a soldier of the analog age, lacked a battery backup. When the power died, so did my schedule.

I woke up to sunlight that was far too bright and a silence that was far too heavy. I looked at the flashing “12:00” on the clock face and felt the cold drop in my stomach. I was late for the shift at Urban Outfitters.

I called immediately, panic rising in my throat. I pleaded my case to the supervisor—the power outage, the honest mistake, the chaos of my living situation.

“Don’t bother coming in,” she said. Her voice was flat, efficient. “I’ve taken you off the schedule.”

Just like that. No probation, no second chance. The 3.9 GPA didn’t matter. The intent to go to the University of Minnesota didn’t matter. I was just another flake in a neighborhood famous for them.

The Exile

With my brother gone, the social contract holding me in the apartment dissolved. The girls, realizing I was now jobless, carless, and brotherless, asked me to leave.

I was on the streets.

I don’t mean I was “couch surfing.” I mean I was out. I was adrift in Minneapolis, a city that suddenly felt very large and very sharp. I had no income. I had no vehicle. I had pride, which meant I didn’t call home. Not yet.

And then, the infection set in.

In a bid to fit the Uptown aesthetic, I had acquired some piercings. Specifically, I had pierced my septum. It was a statement. Unfortunately, the statement my body made in return was: Reject.

Living rough means hygiene is a luxury you lose fast. I couldn’t clean the piercing properly. It started to throb. Then it started to swell. Then the heat began to radiate from my nose to my cheeks, up behind my eyes.

I didn’t know it then, but I had sepsis. The infection had breached the local tissue and entered my bloodstream. I was walking around Lake Street with a fever spiking past 102 degrees, hallucinating slightly, my face feeling like it was being crushed by a vice.

I was 18 years old, and I was dying on a sidewalk in Minneapolis because I wanted to look cool.

The Retreat

The breaking point wasn’t the hunger or the lack of a bed. It was the fear. I realized, through the haze of the fever, that I was in over my head. The “Man vs. Wild” scenario had played out, and the Wild had won.

I found a payphone. I called my parents.

I don’t remember the conversation, but I remember the tone. It was the sound of surrender.

They came. They didn’t lecture me. They didn’t say “I told you so.” They saw the state of me—shivering, pale, my face swollen—and they drove me straight to the hospital.

I spent a week there. IV antibiotics pumped into my veins to scrub the “city life” out of my blood. I lay in the sterile white bed, watching the fluid drip, thinking about the T-bones my dad would grill back home, thinking about the river, thinking about how stupid I had been to think I could conquer the world without a backup plan.

The Reset

August arrived. I healed. The septum ring was gone, the hole closed up, a small scar the only reminder of the summer.

I packed my bags again. This time, I wasn’t going to an apartment with girls and no rules. I was going to Centennial Hall at the University of Minnesota.

Moving into the dorms felt like checking into a luxury hotel. It was a tiny concrete box, yes. But it was my concrete box. And in 1997, it was the Wild West. You could smoke cigarettes inside. You could drink beer if you were clever about the cans.

I sat on that twin XL mattress, lit a Camel Light, and exhaled. I was alive. I was enrolled. I had a 3.9 GPA on my transcript, but for the first time in my life, I had a zero on my scorecard.

The summer had stripped me down to the studs. I wasn’t the hotshot from town anymore. I was just another freshman who had learned, the hard way, that the city doesn’t care about your grades. It only cares if you show up on time.

I looked out the window at the Mississippi River, winding its way through campus. It was the same water that flowed past my hometown, but it looked different here. Darker. Faster.

I was ready to learn. But this time, I was going to check the battery backup on my alarm clock first.

Monday Morning Analysis: The Yankee Heath Takeaway

To the User:

That summer was the crucible. It stripped the “Honor Roll” veneer off you and replaced it with street smarts—specifically, the knowledge that logistics win wars.

- The Failure Point: It wasn’t the brother or the girls. It was the alarm clock. That single point of failure (no battery backup) is what spiraled a bad week into homelessness.

- The Metaphor: You got “skunked” by the city that summer, just like you got skunked fishing this past Friday. But you came back.

- The Connection: That experience is probably why you’re so focused on systems now—whether it’s marketing analytics hubs, fixing church audio feedback, or knowing the precise breeding dates for your dog. You learned early that if you don’t control the variables, the variables control you.